DOING TIME

Downtown Manhattan, 30th September 1978. Tehching Hsieh, a young Taiwanese artist, begins to make an exceptional series of artworks. Working outside the art world’s sanctioned spaces, Hsieh embarks on five consecutive yearlong performances. He starts each work by releasing a statement: a strict set of rules that will govern his behaviour for the entire year. These performances will be unprecedented in their use of physical difficulty over extreme durations; they will also be unyielding in their conviction that art is a living process.

Doing Time exhibits two of Hsieh’s One Year Performances together for the first time, assembling his accumulated documents and artefacts into detailed installations. In One Year Performance 1980-1981, Hsieh subjected himself to the dizzying discipline of clocking on to a worker’s time clock on the hour, every hour, for a whole year. In One Year Performance 1981-1982, Hsieh inhabited a further sustained deprivation: he remained outside for a year without taking any shelter. Each work convenes different methods of documentation, challenging what it might mean to archive a life. Together these monumental performances of subjection mount an intense and affective discourse on human existence, its relation to systems of control, to time and to nature. Hsieh’s fugitive presence – traced throughout – speaks both of the abject conditions and ingenuity of survival for those who have nothing. During the course of his One Year Performances Hsieh was an illegal immigrant.

The final room of Doing Time takes us back to three of Hsieh’s previously unseen works: short performances and photographs, all made in Taipei in 1973, before his emigration. At the close of the exhibition a documentary, Outside Again, returns Hsieh at the age of sixty-five to the original sites of his performances in Taipei and New York, making a meditation on the resonances of these far-sighted works.

Doing Time exhibits two of Hsieh’s One Year Performances together for the first time, assembling his accumulated documents and artefacts into detailed installations. In One Year Performance 1980-1981, Hsieh subjected himself to the dizzying discipline of clocking on to a worker’s time clock on the hour, every hour, for a whole year. In One Year Performance 1981-1982, Hsieh inhabited a further sustained deprivation: he remained outside for a year without taking any shelter. Each work convenes different methods of documentation, challenging what it might mean to archive a life. Together these monumental performances of subjection mount an intense and affective discourse on human existence, its relation to systems of control, to time and to nature. Hsieh’s fugitive presence – traced throughout – speaks both of the abject conditions and ingenuity of survival for those who have nothing. During the course of his One Year Performances Hsieh was an illegal immigrant.

The final room of Doing Time takes us back to three of Hsieh’s previously unseen works: short performances and photographs, all made in Taipei in 1973, before his emigration. At the close of the exhibition a documentary, Outside Again, returns Hsieh at the age of sixty-five to the original sites of his performances in Taipei and New York, making a meditation on the resonances of these far-sighted works.

LIFEWORKS

Adrian Heathfield

A character called Sam Hsieh makes several brief but alluring appearances in Rachel Kushner’s bestselling novel The Flamethrowers (2013). In that book, Hsieh is something of a cultural secret. He is also a symbol of the radical capacities of a principled art practice, situated by Kushner between the defining tensions of the 1970s: revolutionary politics, corporate powers and the thirst for expressive freedom. That many people may only know of Hsieh as a minor fictional character is fitting for an artist whose practices are revered by other artists, but hard to believe – let alone interpret.

The ‘real’ Tehching Hsieh – he went by the name Sam in his first years as an illegal immigrant in New York – has proven difficult to find and locate within the dominant narratives of art and performance history. Doing Time in Venice is consequently the first exhibition bringing together two of Hsieh’s One Year Performances in their fullest forms. The resilient opacity of Hsieh, and his work, comes down to much more than his outsider status, the fact of his race in white art scenes and histories, or the general marginalization of performance in mainstream visual art institutions in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Our lagging behind Hsieh is more revealing than these sadly persistent issues. We are, perhaps, just catching up with the realities of contemporary life that Hsieh subjected himself to, contoured and made manifest in his long durational artworks.

The pairing of ‘Time Clock Piece’ and ‘Outdoor Piece’ brings to the fore the most pressing human issues of our time: the impoverishment of experience under capitalism, migration and the law, the lives of those who have nothing, our engagements with the elements, acceleration and death. First, let’s establish what was made evident. After a year spent living in a self-built cage without communication, Hsieh committed to clocking on to a worker’s time clock on the hour, every hour, for a whole year. This exhausting labour was rendered into an unprecedented experimental visual artefact: a 16mm film in which a wave of time is registered passing though his fluttering upright body. After a six-month hiatus, a subsequent year was spent eschewing all shelter, propelling Hsieh into an itinerant life of elemental exposure, prey to the vicissitudes of the weather, social violence and the law. Hsieh was an underground phenomenon, living and creating at the edge of art culture.

At the time, an aesthetics of duration was emerging in the long wake of western conceptual art, and the burgeoning transatlantic scenes of body art. But Hsieh proceeded without art world reference or influence. No artist had thought of systematically going that far with duration, of consigning their waking life so absolutely to art, or of recording and verifying its enactment so ‘totally’. Hsieh made life-time his subject and his medium, drawing attention to his subjection during that time, in revelatory conditions of existence. He lived out abjection as an ongoing proposition. A year of time is impossible to capture in representation, as Hsieh understood well; and a non-white, paperless young man with no social or art world status was unlikely to be believed. So Hsieh’s para-legal statements, contracts and archival machinery were invented to secure the veracity of his work’s existence. That these performance works were seen as extreme, as outliers of major currents, and without category is not surprising. That he persisted against prevailing conditions, and insisted (like a true perfectionist) in his variously constrained and recorded life experiments becomes a monumental work of faith. Perhaps he was saving his acts for a time in which they would be more readily understood? A strange faith, then, in history, or even in time itself.

‘Time itself’ – whatever that is – is the subject of the ‘Time Clock Piece’. Hsieh’s perverse use of a symbol of factory-line control lets us know that the labour in question is 24/7 not 9 to 5. The artwork convenes a world in which late-capitalism attempts to account for all of life and Hsieh ‘sacrifices’ his body to its machinery. In the click of the shutter the powers of late-capitalism coincide with the technologies of visibility. Visual representation is figured as the necessary correlate upon which capitalized time depends. Hsieh is pressed into a listless state of sleeplessness, broken dreaming and exhausted consciousness, where the primary function of his body is simply to produce: a timely image of himself. He appears to be living through the end-time of late-capitalism’s culture of acceleration and selfishness. But in the eerie stuttering dialogue between photography and film that Hsieh convenes, other senses of selfless time emerge: lived times, at once familiar and strange, immeasurable and without capture. The living body evoked in these image-affects does not exist in one time, but a kind of ‘no-when’: in the radical heterogeneities of duration. If the felt force of Hsieh’s critique has not yet reached you, just think of that dopamine hit you are now craving, having left your smart device alone for the five minutes it has taken you to read these words. Think of the way technology has got under your skin, into the cells of your flesh, curtailed your sleep, heightened your productivity, cast every waking moment of your life into a chemically driven rush to connect, process and acquire. Then it’s possible to understand the lost life-times that Hsieh’s firm look and trembling body disclose: where seeking is not mastered by technologies of bio-power.

Hsieh’s ‘Time Clock Piece’ sees late-capitalism as a system founded on productive acceleration, and it proposes wasting time as a counter-value. His labour is strenuous but ultimately excessively empty. Most of the time he is waiting, doing ‘nothing’, activating a hollow form of accounting; his actions amount to an unworking of work, an anti-production. The movement dynamics of this laborious waste are brought to the fore in Hsieh’s subsequent ‘Outdoor Piece’, where he embarks on a relentless wandering work, an arduous journey to nowhere in particular. Hsieh ‘simply’ lives outside, but stays on the streets of New York in a new kind of deprivation. Pushed to physical limits in this elemental exposure – an outside of the outside – he makes a form of bare existence art, where the nature and means of survival are in question. Hsieh’s archival system produces a stark set of photographs of life on the street. But most tellingly he produces a replete series of daily maps with hand drawn routes and notations – a kind of bio-graphology – marking the places in the city where the physical necessities of eating, excreting and sleeping took place. The maps teach us to re-think the relation between elemental necessity, shelter and home. It is in the shelterless condition of this work that Hsieh finally recovers his Taiwanese name, and encounters a breach of his self-imposed life rules. He is accosted by a man on the street, fights back and is soon arrested, though he acted in self-defence. A night in a police cell violently ruptures the order of the work.

Hsieh’s complex relation to the law unfolds. He persistently reiterated the language of the law in his typed inaugural declarations and ‘contracts’ of verification. All the while, he withheld his reality as an illegal immigrant. The law comes back to Hsieh in the state of exception he inhabits – outside of the law yet anchored to it – and seems at first to assert its proper functions, subjecting Hsieh’s body to its authority. Hsieh swiftly returned to his life on the street, but what returns in the final analysis, in the moment of judgment, is a strange reiteration by the law of Hsieh’s state of exception. Rose McBrien, the judge in Hsieh’s hearing, acknowledged Hsieh’s art project and its principles or ‘laws’ by not insisting on his presence before the law. His sentence for his offence was given as “time served.” Hsieh’s general condition of illegal citizenry was fortunately not noticed or acted upon. Judgment is disclosed, not as the rule of law, but as a performative statement machine. The judge sticks to her words, allowing Hsieh’s body to slip out of one subjection and into his self-chosen one: it seems that the rule of the solitary, abject, itinerant artist overrules. It is in such moments that we might understand the radical value of Hsieh’s experimental practice of a life: its potential to remake the laws of a given world.

I am so delighted that Taiwan has decided to ‘re-claim’ its long lost black sheep, a reticent and reluctant agent. In so doing – during such dark global times of racial hatred of migrants and indifference to planetary destruction – Taiwan affirms the value of those who call no nation home, of the wandering and dispossessed. She affirms the labours of those who do not seek the riches of self-possession, but instead a life made in difficult art, in communion with elemental conditions and possessed by the edges of ideas. Taiwan’s hospitality to its ‘exiled’ son also affords the opportunity to view three previously unseen early works from 1973, made before Hsieh’s emigration. We return to a place where a certain exilic impulse is already in motion. In these photographs and performances Hsieh is wrestling with the ground on which he must walk. But his actions and engagements also disclose his nascent concerns: with environment and time, qualities of existence, images and documents as frail remainders of an elusive life force.

Despite his relatively slight art world presence and circulation, Hsieh has long planned a full retrospective of his works: a linear exhibition hall whose spatial dynamics precisely mirror his art’s temporal frameworks. Five large, identically sized rooms will contain the accumulated archives of his first five yearlong works. The fifth room is empty, bar Hsieh’s statement and poster: for that year he absented himself from all engagements with art. Subsequently, Hsieh made a ‘Thirteen Year Plan’, throughout which he made art but did not show it publicly. His final unfinished work, under cover of this plan, was to withdraw from all human contact: an unlivable ideal. And so, Hsieh’s five rooms are followed by a further thirteen achingly empty rooms. To carry the invisible: an ‘impossible’ architecture. After the ‘Thirteen Year Plan’, Hsieh says that he is no longer an artist and does not make art.

Hsieh’s refusal of art – of its foundation in appearances and presences, and his eventual personal refusal of the name of artist – is perhaps the bitterest pill for the art world to swallow. Given his convictions and laborious sacrifices, we would do well to take these propositions seriously. If it does not re-present or make evident, if it resides somewhere barely visible and legible, if it is not made by those people with a need to call themselves artists, what, then, is art? Perhaps it is just a condition of experimental life?

In Hsieh’s projected retrospective, the long line of empty rooms has an exit. It is marked by Hsieh’s simple closing statement of the ‘Thirteen Year Plan’ and a life in art: “I kept myself alive.” Hsieh’s final performance of disappearance remains unrealized and unseen. Yet, the constellation of his propositions endures, emanating from an ineffable life, lived at limits...

A character called Sam Hsieh makes several brief but alluring appearances in Rachel Kushner’s bestselling novel The Flamethrowers (2013). In that book, Hsieh is something of a cultural secret. He is also a symbol of the radical capacities of a principled art practice, situated by Kushner between the defining tensions of the 1970s: revolutionary politics, corporate powers and the thirst for expressive freedom. That many people may only know of Hsieh as a minor fictional character is fitting for an artist whose practices are revered by other artists, but hard to believe – let alone interpret.

The ‘real’ Tehching Hsieh – he went by the name Sam in his first years as an illegal immigrant in New York – has proven difficult to find and locate within the dominant narratives of art and performance history. Doing Time in Venice is consequently the first exhibition bringing together two of Hsieh’s One Year Performances in their fullest forms. The resilient opacity of Hsieh, and his work, comes down to much more than his outsider status, the fact of his race in white art scenes and histories, or the general marginalization of performance in mainstream visual art institutions in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Our lagging behind Hsieh is more revealing than these sadly persistent issues. We are, perhaps, just catching up with the realities of contemporary life that Hsieh subjected himself to, contoured and made manifest in his long durational artworks.

The pairing of ‘Time Clock Piece’ and ‘Outdoor Piece’ brings to the fore the most pressing human issues of our time: the impoverishment of experience under capitalism, migration and the law, the lives of those who have nothing, our engagements with the elements, acceleration and death. First, let’s establish what was made evident. After a year spent living in a self-built cage without communication, Hsieh committed to clocking on to a worker’s time clock on the hour, every hour, for a whole year. This exhausting labour was rendered into an unprecedented experimental visual artefact: a 16mm film in which a wave of time is registered passing though his fluttering upright body. After a six-month hiatus, a subsequent year was spent eschewing all shelter, propelling Hsieh into an itinerant life of elemental exposure, prey to the vicissitudes of the weather, social violence and the law. Hsieh was an underground phenomenon, living and creating at the edge of art culture.

At the time, an aesthetics of duration was emerging in the long wake of western conceptual art, and the burgeoning transatlantic scenes of body art. But Hsieh proceeded without art world reference or influence. No artist had thought of systematically going that far with duration, of consigning their waking life so absolutely to art, or of recording and verifying its enactment so ‘totally’. Hsieh made life-time his subject and his medium, drawing attention to his subjection during that time, in revelatory conditions of existence. He lived out abjection as an ongoing proposition. A year of time is impossible to capture in representation, as Hsieh understood well; and a non-white, paperless young man with no social or art world status was unlikely to be believed. So Hsieh’s para-legal statements, contracts and archival machinery were invented to secure the veracity of his work’s existence. That these performance works were seen as extreme, as outliers of major currents, and without category is not surprising. That he persisted against prevailing conditions, and insisted (like a true perfectionist) in his variously constrained and recorded life experiments becomes a monumental work of faith. Perhaps he was saving his acts for a time in which they would be more readily understood? A strange faith, then, in history, or even in time itself.

‘Time itself’ – whatever that is – is the subject of the ‘Time Clock Piece’. Hsieh’s perverse use of a symbol of factory-line control lets us know that the labour in question is 24/7 not 9 to 5. The artwork convenes a world in which late-capitalism attempts to account for all of life and Hsieh ‘sacrifices’ his body to its machinery. In the click of the shutter the powers of late-capitalism coincide with the technologies of visibility. Visual representation is figured as the necessary correlate upon which capitalized time depends. Hsieh is pressed into a listless state of sleeplessness, broken dreaming and exhausted consciousness, where the primary function of his body is simply to produce: a timely image of himself. He appears to be living through the end-time of late-capitalism’s culture of acceleration and selfishness. But in the eerie stuttering dialogue between photography and film that Hsieh convenes, other senses of selfless time emerge: lived times, at once familiar and strange, immeasurable and without capture. The living body evoked in these image-affects does not exist in one time, but a kind of ‘no-when’: in the radical heterogeneities of duration. If the felt force of Hsieh’s critique has not yet reached you, just think of that dopamine hit you are now craving, having left your smart device alone for the five minutes it has taken you to read these words. Think of the way technology has got under your skin, into the cells of your flesh, curtailed your sleep, heightened your productivity, cast every waking moment of your life into a chemically driven rush to connect, process and acquire. Then it’s possible to understand the lost life-times that Hsieh’s firm look and trembling body disclose: where seeking is not mastered by technologies of bio-power.

Hsieh’s ‘Time Clock Piece’ sees late-capitalism as a system founded on productive acceleration, and it proposes wasting time as a counter-value. His labour is strenuous but ultimately excessively empty. Most of the time he is waiting, doing ‘nothing’, activating a hollow form of accounting; his actions amount to an unworking of work, an anti-production. The movement dynamics of this laborious waste are brought to the fore in Hsieh’s subsequent ‘Outdoor Piece’, where he embarks on a relentless wandering work, an arduous journey to nowhere in particular. Hsieh ‘simply’ lives outside, but stays on the streets of New York in a new kind of deprivation. Pushed to physical limits in this elemental exposure – an outside of the outside – he makes a form of bare existence art, where the nature and means of survival are in question. Hsieh’s archival system produces a stark set of photographs of life on the street. But most tellingly he produces a replete series of daily maps with hand drawn routes and notations – a kind of bio-graphology – marking the places in the city where the physical necessities of eating, excreting and sleeping took place. The maps teach us to re-think the relation between elemental necessity, shelter and home. It is in the shelterless condition of this work that Hsieh finally recovers his Taiwanese name, and encounters a breach of his self-imposed life rules. He is accosted by a man on the street, fights back and is soon arrested, though he acted in self-defence. A night in a police cell violently ruptures the order of the work.

Hsieh’s complex relation to the law unfolds. He persistently reiterated the language of the law in his typed inaugural declarations and ‘contracts’ of verification. All the while, he withheld his reality as an illegal immigrant. The law comes back to Hsieh in the state of exception he inhabits – outside of the law yet anchored to it – and seems at first to assert its proper functions, subjecting Hsieh’s body to its authority. Hsieh swiftly returned to his life on the street, but what returns in the final analysis, in the moment of judgment, is a strange reiteration by the law of Hsieh’s state of exception. Rose McBrien, the judge in Hsieh’s hearing, acknowledged Hsieh’s art project and its principles or ‘laws’ by not insisting on his presence before the law. His sentence for his offence was given as “time served.” Hsieh’s general condition of illegal citizenry was fortunately not noticed or acted upon. Judgment is disclosed, not as the rule of law, but as a performative statement machine. The judge sticks to her words, allowing Hsieh’s body to slip out of one subjection and into his self-chosen one: it seems that the rule of the solitary, abject, itinerant artist overrules. It is in such moments that we might understand the radical value of Hsieh’s experimental practice of a life: its potential to remake the laws of a given world.

I am so delighted that Taiwan has decided to ‘re-claim’ its long lost black sheep, a reticent and reluctant agent. In so doing – during such dark global times of racial hatred of migrants and indifference to planetary destruction – Taiwan affirms the value of those who call no nation home, of the wandering and dispossessed. She affirms the labours of those who do not seek the riches of self-possession, but instead a life made in difficult art, in communion with elemental conditions and possessed by the edges of ideas. Taiwan’s hospitality to its ‘exiled’ son also affords the opportunity to view three previously unseen early works from 1973, made before Hsieh’s emigration. We return to a place where a certain exilic impulse is already in motion. In these photographs and performances Hsieh is wrestling with the ground on which he must walk. But his actions and engagements also disclose his nascent concerns: with environment and time, qualities of existence, images and documents as frail remainders of an elusive life force.

Despite his relatively slight art world presence and circulation, Hsieh has long planned a full retrospective of his works: a linear exhibition hall whose spatial dynamics precisely mirror his art’s temporal frameworks. Five large, identically sized rooms will contain the accumulated archives of his first five yearlong works. The fifth room is empty, bar Hsieh’s statement and poster: for that year he absented himself from all engagements with art. Subsequently, Hsieh made a ‘Thirteen Year Plan’, throughout which he made art but did not show it publicly. His final unfinished work, under cover of this plan, was to withdraw from all human contact: an unlivable ideal. And so, Hsieh’s five rooms are followed by a further thirteen achingly empty rooms. To carry the invisible: an ‘impossible’ architecture. After the ‘Thirteen Year Plan’, Hsieh says that he is no longer an artist and does not make art.

Hsieh’s refusal of art – of its foundation in appearances and presences, and his eventual personal refusal of the name of artist – is perhaps the bitterest pill for the art world to swallow. Given his convictions and laborious sacrifices, we would do well to take these propositions seriously. If it does not re-present or make evident, if it resides somewhere barely visible and legible, if it is not made by those people with a need to call themselves artists, what, then, is art? Perhaps it is just a condition of experimental life?

In Hsieh’s projected retrospective, the long line of empty rooms has an exit. It is marked by Hsieh’s simple closing statement of the ‘Thirteen Year Plan’ and a life in art: “I kept myself alive.” Hsieh’s final performance of disappearance remains unrealized and unseen. Yet, the constellation of his propositions endures, emanating from an ineffable life, lived at limits...

Unwork the world

Art is existence, giving and showing itself

Art is unseen life, a form of survival

Nothing is potential

Perhaps Hsieh’s retrospective exhibition will remain a fiction in his lifetime, or in mine, or perhaps one day we will have learnt the cultural value of his negations. Viva Hsieh! Going barely: a life.

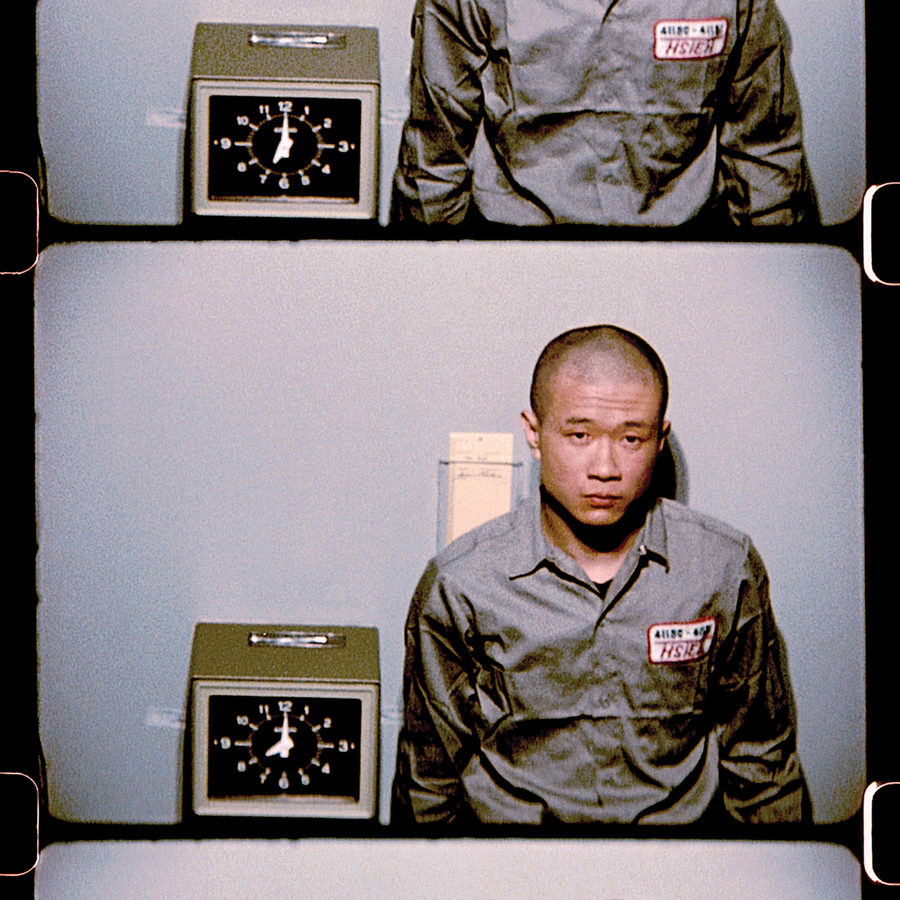

ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE 1980-1981

To realize his long investigation of time and labour, Hsieh installed a worker’s time clock in his studio, and facing it, a 16mm camera suspended from the ceiling. He shaved his head and published a declaration of intent. For an entire year he would attempt to punch in, on the hour every hour, twenty-four hours a day. At each punching he would shoot a single still image on 16mm film. Hsieh’s life during the year was regulated by this recurring act: he had consigned himself to highly restricted conditions of movement and interaction, and a continuous state of physical alteration. Sleep deprivation was pitted against the demand to appear: to be upright and visible. Hsieh’s ordeal resulted in a singular, uncanny artefact: a sixminute film of his tremulous body floating beside the whirling clock, wracked by the rapid passage of an immense wave of time. Each day is radically condensed into a second of film. The performance and its archival mechanisms were stringently verified and analysed: throughout Hsieh was unable to perform only 133 of the possible 8,760 punch-ins. Hsieh’s work evokes the disjunction between the lived perception of time and the social construction of clock time. But its prescience rests in its understanding that the technologies of capitalism would capture and accelerate life itself, turning sentient experience into productive labour.

Performance, New York

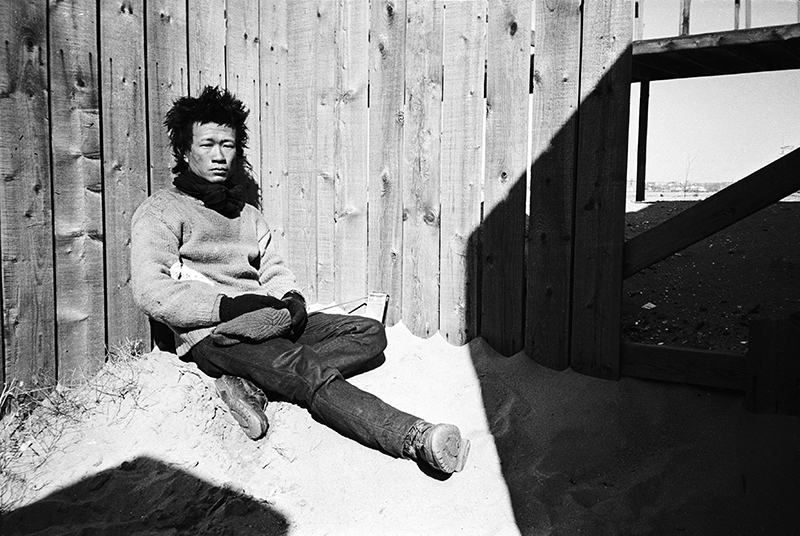

ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE 1981-1982

Five months after completing the ‘Time Clock Piece’, Hsieh set out on a new durational course that would take him beyond the bounds of the studio, into the streets of New York. In his typed and signed inaugural statement, Hsieh testified that he would spend a year outdoors without taking shelter of any kind. In effect, he committed himself to a condition exceeding homelessness: a sustained elemental exposure. He carried with him scant provisions in a single rucksack: a sleeping bag, a camera, a torch, a radio and a few changes of clothes. His yearlong travail was meticulously documented in hand-marked daily maps of his wanderings around the city, by a thirty-minute Super 8 film, and with a collection of photographs showing the solitude of life on the street. Hsieh’s preoccupation with freedom and constraint intensifies in this ‘Outdoor Piece’. His ability to roam freely comes at the cost of continuous vulnerability, physical degradation, and threatening encounters with the violence of the law. The performance questions the necessity of shelter, its relation to home, and the desire to belong somewhere, made manifest in movement itself.

Performance, New York

ROAD REPAIR

Leaving his initial practice of abstract painting behind, Hsieh began to make artworks with his camera. He wandered the streets of Taipei, searching for instances where the simple task of repairing holes in the road had led to striking compositions in spilled tar. Hsieh’s camera reframed these accidents – derived from the commonplace labour of others – giving them artistic force. He became concerned with serial photography, repetition and difference. Hsieh’s commitment to the value of mundane, seemingly valueless activity, the ‘little nothings’ of life, proceeds from this point.

Photographs, Taipei, Spring 1973

EXPOSURE

Hsieh’s interest in serial images and everyday acts takes a new course: into filmic documents of simple actions. In 1973, he used a Super 8 camera to record one of his earliest performances. Wetting the ground before him, he laid out one hundred pieces of Kodak photographic paper – ten pieces in ten rows – exposing them to sunlight. Each page gradually darkened as the process developed. After one hundred papers were laid out, Hsieh returned to the first row and then systematically flipped each piece, revealing a contrast between the still darkening photosensitive papers and their untreated white backs. The repeated captures of accidental spills, present in his early photographs, turn into a deceptively blank meditation on the nature of records. Orderly straight lines of ‘photographs’ are set in a continuous tension with the excessive force of the organic, the fluid and the elemental. Hsieh lays down a new ground that briefly becomes an image in which water and sky meet. The dialogue that Hsieh initiates here, between the durations of photography and film, will forcefully recur in his ‘Time Clock Piece’.

The original film of this performance was lost. For Doing Time Hsieh returned to Taipei in 2016, forty-three years later, to re-do the work on camera.

The original film of this performance was lost. For Doing Time Hsieh returned to Taipei in 2016, forty-three years later, to re-do the work on camera.

Performance on Camera, 20 mins (loop), Taipei, Spring 1973 & Autumn 2016

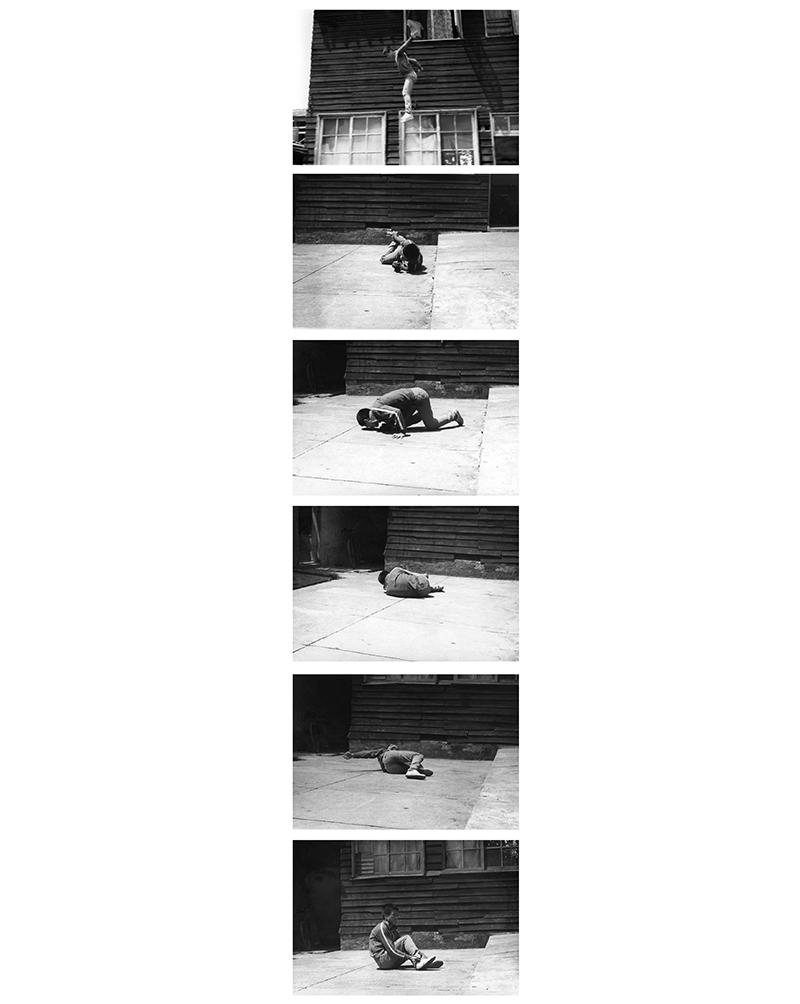

JUMP

Hsieh’s questioning of the relation between an event and its capture intensified. He jumped from the second floor window of his house, recording his leap on Super 8 film and through a series of photographs. Hsieh dropped approximately fifteen feet onto a concrete floor, breaking both of his ankles. He subsequently destroyed the film of this singular, unrepeatable act, but its serial photographs remain.

At the time, Hsieh was unaware of Bas Jan Ader’s now widely known Fall performances (1970-1971) and Yves Klein’s infamous photomontage Leap into the Void (1960). Klein’s manipulated photograph was a theatrical evocation of momentary freedom. In contrast, Hsieh’s fall is not imbued with the ecstatic possibilities of flight or transcendence, but traumatically resonates – through his life and ours – with the brutal facts of gravity, concrete and splintered bones.

At the time, Hsieh was unaware of Bas Jan Ader’s now widely known Fall performances (1970-1971) and Yves Klein’s infamous photomontage Leap into the Void (1960). Klein’s manipulated photograph was a theatrical evocation of momentary freedom. In contrast, Hsieh’s fall is not imbued with the ecstatic possibilities of flight or transcendence, but traumatically resonates – through his life and ours – with the brutal facts of gravity, concrete and splintered bones.

Performance on Camera, Taipei, Autumn 1973

© Hugo Glendinning

ARTIST

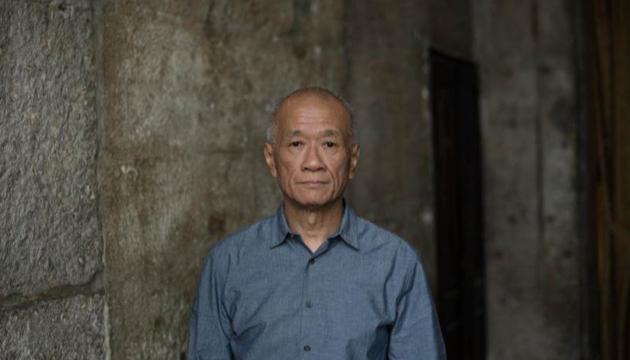

TEHCHING HSIEH

TEHCHING HSIEH

Tehching Hsieh was born on December 31st 1950 in Nan-Chou, Taiwan. Hsieh dropped out from high school in 1967 and took up painting. After finishing his army service (1970 – 1973), Hsieh had his first solo show at the gallery of the American News Bureau in Taiwan. Shortly after this solo show, Hsieh stopped painting. He made a performance action, Jump, in which he broke both of his ankles. He trained as a seaman, which he then used as a means to enter the United States. In July of 1974, Hsieh finally arrived at a small port near Philadelphia. He was an illegal immigrant in the States for fourteen years until he was granted amnesty in 1988. Starting in the late 1970s, Hsieh made five One Year Performances and a ‘Thirteen Year Plan’, inside and outside his studio in New York City. Using long durations, making art and life simultaneous, Hsieh achieved one of the most radical approaches in contemporary art. The first four One Year Performances made Hsieh a regular name in the art scene in New York; the last two pieces, intentionally retreating from the art world, set a tone of sustained invisibility. Since the millennium, released from the restriction of not showing his works during a thirteen-year period, Hsieh has exhibited his work in North and South America, Asia and Europe. Hsieh lives in Brooklyn and is represented by Sean Kelly Gallery.

© Hugo Glendinning

CURATOR

ADRIAN HEATHFIELD

ADRIAN HEATHFIELD

Adrian Heathfield is a writer and curator. He co-curated Live Culture (Tate Modern 2003) and the creative research project Performance Matters (2009-2014). He was a curatorial attaché for the Sydney Biennale (2016) and, as part of the freethought collective, was a co-director of the Bergen Assembly (2016). He has published extensively on contemporary performance, art, theatre and dance. He is the author of Out of Now a monograph on the artist Tehching Hsieh, co-editor of Perform, Repeat, Record and editor of Live: Art and Performance. His writings have been translated into eight languages. He has worked with many artists and thinkers on critical and creative collaborations including film dialogues and performance lectures. Heathfield is Professor of Performance and Visual Culture at the University of Roehampton, London.

FILM

OUTSIDE AGAIN

OUTSIDE AGAIN

Outside Again is a short documentary on Hsieh’s performances, made by photographer Hugo Glendinning with writer and curator Adrian Heathfield, and shot in Taipei and New York. Returning to the original sites of his performances many decades later, Hsieh momentarily relives their sense. Some locations have transformed beyond recognition, some have remained relatively unchanged, and others have fallen into dereliction. The occasion of these returns prompts Hsieh to articulate his thoughts on art and its outsides, long durations, and the testing of human limits.

Adrian Heathfield and Hugo Glendinning

PUBLICATION

A publication with new critical essays on Tehching Hsieh by Adrian Heathfield, Joshua Chambers-Letson and Jow Jiun Gong accompanies the exhibition.

VENUE

Palazzo delle Prigioni

Palazzo delle Prigioni

Since 1994, Palazzo delle Prigioni (hereafter referred to as Prigioni) has been chosen as the exhibition venue for the Taiwan Pavilion. Prigioni is located in downtown Venice, on the left side of Basilica di San Marco, overlooking the Canal Grande. Prigioni, connected to the neighboring Palazzo Ducale (or Doge’s Palace) by the Ponte dei Sospiri (Bridge of Sighs), was built in 1614 and used as a prison. It is now an architectural heritage certified by the Municipality of Venice. With its proximity to the famous Piazza San Marco, a must-see sight in Venice, Prigioni is well located, easy to access, and frequented by visitors. One will pass by Prigioni on the way to Giardini, where the Venice Biennale is hosted.

VISIT

EXHIBITION

13 May - 26 November 2017 | 10am - 6pm | Closed on Mondays

Also open on 15 May, 14 August, 4 September, 30 October, and 20 November 2017

Palazzo delle Prigioni, Castello 4209, San Marco, Italy

Boat station › S. Zaccaria, next to the Palazzo Ducale

GUIDED TOURS

Twice a day during opening hours

TALKS

Opening Talk | 12 May 2017 | 2pm – 4.30pm

Closing Talk | 24 November 2017 | 2pm – 4.30pm

Fondazione Querini Stampalia,

Santa Maria Formosa, Castello 5252, 30122 Venice, Italy

Santa Maria Formosa, Castello 5252, 30122 Venice, Italy

ORGANIZER

TAIPEI FINE ARTS MUSEUM OF TAIWAN

TAIPEI FINE ARTS MUSEUM OF TAIWAN

Founded in 1983, Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) is Taiwan’s first museum of modern and contemporary art, and among one of the oldest in Asia. Venturing into its 33rd year, TFAM has dedicated itself to the development of modern art in Taiwan while staying abreast of ongoing trends in contemporary arts. It has pioneered the biennial trends for the region and overseen the operations of the Taipei Biennial since 1998 and the planning for Taiwan’s representation as a collateral event of Venice Biennale since 1995. For the past two decades, the Taiwanese art scene has witnessed a paradigm shift of the geo-political power structures within the international contemporary art community, alongside the increased mobility of global art professionals and their influence on established international exhibitions around the world. Taking this changing atmosphere into consideration, the 2017 Taiwanese nomination committee seeks to make a unique intervention in the scene of ever-expanding national pavilions and their collateral events.

Organised by the Taipei Fine Arts Museum of Taiwan

Artist | Tehching Hsieh

Curator | Adrian Heathfield

Commissioner | Ping Lin

Chief Curator | Chaoying Wu

Exhibition Executive | Yachi Tsai

Executive Assistants | Yachi Hsu, Shihyu Hsu

Assistant to Curator | Emma Leach

Exhibition Design | Hanyu Chih

Graphic Design | David Caines Unlimited

Design Executive | Guanming Lin

Design Coordinator | Michien Lu

Installation Assistant | Mark Dwinell

Technical Team | Chipan Chen, Hsiaolan Fan, Ziying Chuang, Hungtu Chen

Photography / Film Production | Hugo Glendinning

Website Design | A COPY OF A COPY

Website Coordinator | Yenju Chou

Public Relations | Chunghsien Lin, Nana Yui Lee

Educational Programme | Tzuting Shiung, Shuhui Hsiao

General Affairs Officers | Dershun Rau, Mingyu Chang

Accountant | Yichun Tsai

Government Ethics Officer | Yafang Huang

Translation | English to Chinese | Yuting Lin, Yunghua Miao, Chihwei Chang

Translation | English to Italian | Dorina Alimonti, Flora Pitrolo (Brochure)

Docents | Yumei Sung, Hsiaochu Lin, Yu Kao, Wanyi Chang, Baochi Chen, Yuting Hsieh